The Contexts of Persecution

Persecution in the religious sense always involves a severe violation of the human right to religious freedom. Guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and other major international legal conventions, the human right to religious freedom declares the moral and civic immunity of individuals and religious communities from coercion or violence on account of their religious beliefs and practice. It protects their structures of governance, their property, their schools, their charities, the public communication of their message, and their contributions to the political life of their respective societies, especially in matters touching upon justice and the common good.

Dr. Charles Tieszen defines religious persecution as “any unjust action of varying levels of hostility directed to religious believers through systematic oppression or through irregular harassment or discrimination resulting in various levels of harm as it is considered from the victim’s perspective, each action having religion as its primary motivator.” Modes of persecution include arbitrary detention, coercive and unjust interrogation, forced labor, imprisonment, beating, torture, disappearance, forced flight from homes, enslavement, rape, murder, unjust execution, attacks on and destruction of churches, and credible threats to carry out such actions. Often, law and policy authorize or encourage persecution, for instance through blasphemy laws, onerous religious registration regulations, and laws outlawing proselytism. This definition of persecution includes forms of severe discrimination in which religious minorities are denied jobs or positions in the economic sphere or in government, or are otherwise stigmatized within societies by private groups. Discrimination is a highly unjust form of unequal treatment that can impoverish entire communities. It often leads to violence.

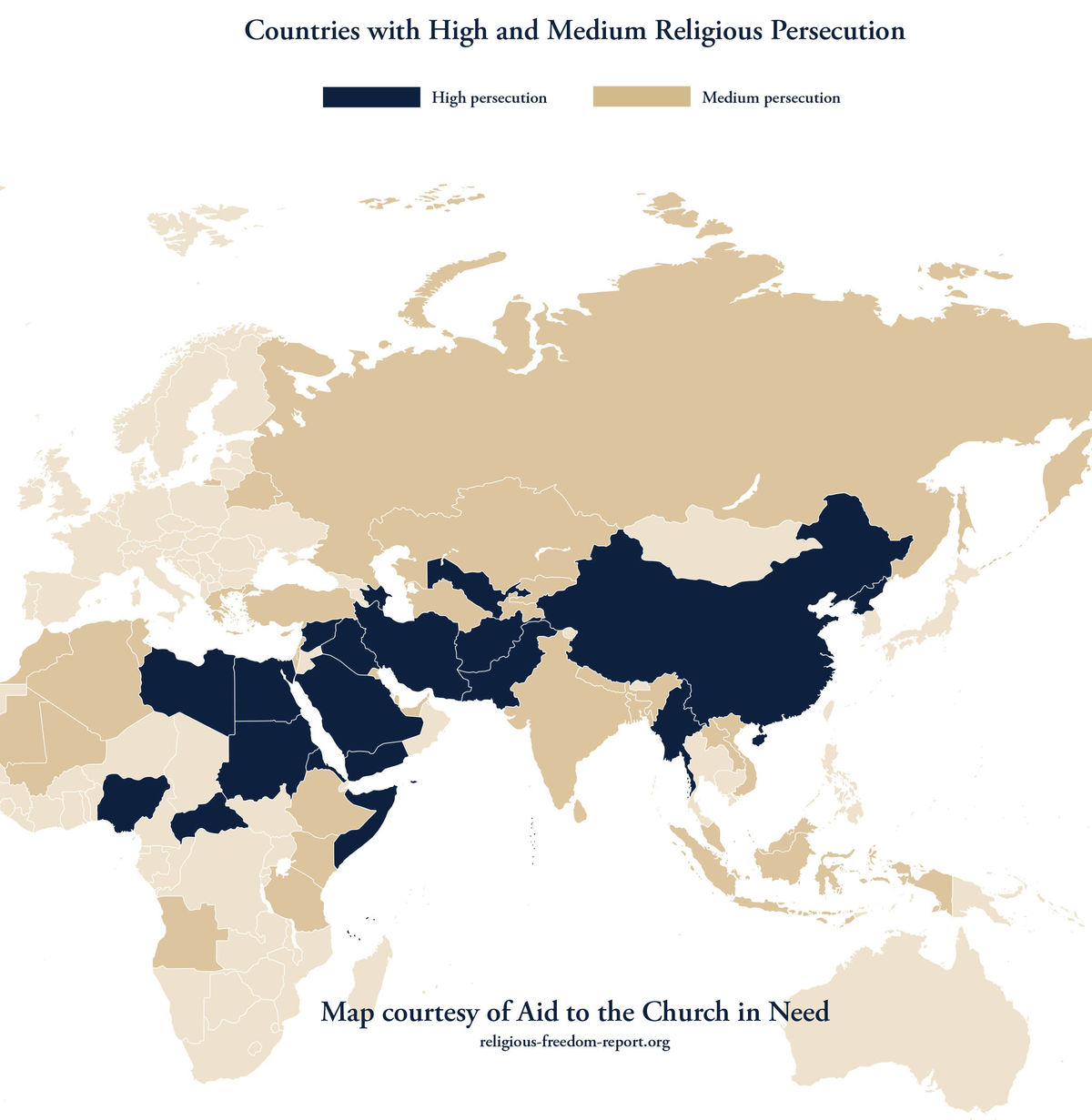

As the following map shows, most of the world’s persecution of Christians takes place within a geographic band that begins around Libya, moves eastward to Egypt and the rest of the Middle East, expands north to Russia and south to Sri Lanka, and then proceeds eastward to China, Indonesia, and North Korea. Outside of this band are several other repressive regimes, like Cuba.

In most of these countries, Christians are small minorities lacking demographic strength and political clout. There are exceptions, such as Russia; there, while the majority is Orthodox Christian, minority Christian churches and religious sects experience strong discrimination. Anomalous, too, is Cuba, where Catholic Christians constitute a majority that is nevertheless heavily constricted by the long-standing Communist government. Most of Kenya’s population is Christian and is persecuted by al-Shabaab, an Islamist militant group.

Within the countries studied, who does the persecuting? Although Western commentary regularly blames Islam, the regimes that repress Christians vary widely. Islamist regimes like Saudi Arabia and Iran certainly constitute one type of persecuting state. Communist regimes like China, Vietnam, Laos, Cuba, and North Korea are a second type. India, Sri Lanka, and Russia exemplify a third type, in which various forms of religious nationalism promote a fusion of state, faith, and national identity to the detriment of Christian minorities. A fourth category comprises regimes that impose a harsh secular ideology, such as the post-Soviet republics of Central Asia.

Perhaps surprisingly, democracies sometimes host and even enable violence and harsh discrimination toward Christians. India, the world’s largest democracy, though it has a well-earned reputation for religious peace and healthy pluralism, has elected a Hindu nationalist government with close ties to militant groups that foment violence against the country’s minority Christians and Muslims. Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim democracy, has a broad tradition of religious tolerance, yet its mechanisms of democratic representation and certain sectors of its bureaucracy enable Islamist activists to repress the Christian minority as well as Ahmadiyya and other Muslims.

It is not only “Caesar” (i.e., governments) that wields the sword against Christians. Non-state actors—populations at large and organized groups, including violent religious extremists and terrorist groups—are often responsible for repression, too. The Taliban in Afghanistan, Hindu extremist groups in India, Boko Haram in Nigeria, and al-Shabaab in Somalia and Kenya are examples of organizations that are distinct from the state yet deny the state its characteristic monopoly on the use of violence.

Frequently, Caesar and these “little Caesars” reinforce each other in inflicting persecution. Majority populations intolerant toward minorities buttress the authority of repressive regimes. Reciprocally, regimes that espouse intolerant ideologies provide legitimacy for, tacitly encourage, and sometimes overtly empower extralegal groups that carry out persecution. When a regime’s ideology corresponds to popular culture and attitudes, government and society form a powerful united front against minorities. The Taliban, for instance, springing from the dominant culture of North Pakistan and Afghanistan, is strengthened by the laws of both countries, and is thus a formidable repressor of Afghanistan’s tiny Christian minority. By contrast, when a regime’s ideology is imposed by a dominant elite and does not resonate with the people, then government may carry out repression on its own. In some cases, violent extremist groups actually become Caesar when they form their own governing regime, as did the Islamic State when it came to control and govern vast territory in Iraq and Syria beginning in 2014.

A vivid example of the interplay between state and society comes from Egypt, from June 30, 2012, to July 3, 2013. During that period, the Muslim Brotherhood was in power under President Mohammed Morsi. Although the Brotherhood did not call overtly for the persecution of Egypt’s Coptic Christian minority, which accounts for 5 to 10 percent of the population, it sought to establish a far more conservative form of Sharia law that deepened the Copts’ vulnerability. Previously, under President Hosni Mubarak, who ruled from 1981 until the Arab Uprisings overthrew him in early 2011, Copts had lived a second-class status but received some government protection. Feeling empowered by Morsi, a group of Egyptian Islamic scholars signed a common letter in August 2012 in which they called for the killing of Christians, citing Quran 9:29: “Fight those who believe not in God nor the Last Day.” Hours after Islamists distributed the letter, Muslims began killing Christians in Asyut in Upper Egypt.

Not only is persecution perpetrated by a variety of regimes and actors, it is also manifested in varying degrees of severity. Two organizations dedicated to the cause of persecuted Christians, Aid to the Church in Need and Open Doors, have developed indices for this severity, which are reported in the table on pages 16–17.

Next Page : Varieties of Christian Responses to Persecution